This one is for Dan M and his recent comments...

It's probably truer for me than it is for him though...

This one is for Dan M and his recent comments...

It's probably truer for me than it is for him though...

One of the commonly used techniques by liberal critics of the Bible is linguistic analysis. It's used for other things and by other people too, but I'm mainly talking about that use.

One of the things they do is they look at (for example) Paul's letters, and they look at how often different words and themes occur. They they say (for example) that 1 Timothy looks very different to Romans - Philippians, so wasn't written by Paul. Noowadays, they even use computer programs for it. Or some do - most of them don't seem to know how to work computers...

There are several problems with this method of seeing who wrote what.

One is that it assumes that each author only writes in a single style - Paul might well have written differently when writing to individuals after AD60 to how he wrote when writing to churches before AD60. We know that authors do write in different styles at different times and for different reasons. Has that been factored in?

Could it analyse the novels of Iain M Banks (a science fiction author), and tell me they were all by a different person from Greg Bear (another science fiction author), but by the same person as Iain Banks (a non-science fiction author who is the same person as Iain M Banks). And what would they do with Feersum Enjinn (which is largely written phonetically and in three different styles)? I don't think it would cope; I very much doubt it has been tested.

For working within books, which is how it is often used in the Old Testament (e.g. showing that Isaiah had two or three different authors), have comparable examples been tested? Can it take a Christopher Tolkien novel and say which bits were taken from his father's notes? I doubt it. Could it take a novel by Margaret Atwood or JRR Tolkien, which tend to be written in several styles, and tell me it was the work of a single author, but the Positronic Man by Asimov & Silverberg wasn't? I doubt it.

These theories and methods annoy me. Partly because they aim to undermine stuff I believe, but largely because they're pretending to be scientific, but at the end of the day, they're just bad science.

I've redone the colour scheme. Let me know if you have strong opinions either way on it.

I do like Custard. Hence the name really - it's good on so many levels. It goes really well with almost all cakes (Carrot is the only notable counter-example). It's a wonderful non-Newtonian fluid, with all kinds of interesting colloidal properties. In the right circumstances, it can be used as an explosive.

But that bag contains 1000 servings when full. That's a lot of custard!

Thanks to Su for the photo!

Went to see Transformers this afternoon. Good special effects, two dimensional characters, pointless scenes and plot holes a mile wide, including important topics like the whole purpose of the battle, the side who want to protect people moving the location of the battle to a big city. Enjoyable if and only if you can turn your brain off, and you like explosions.

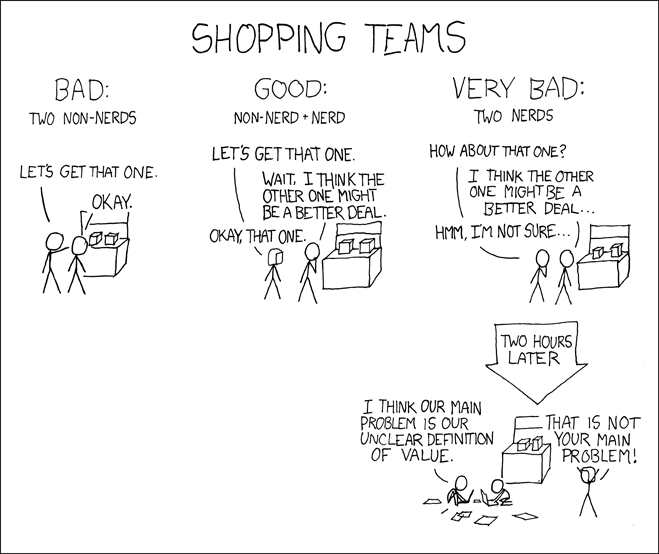

Evidently I on my own function as two nerds when it comes to shopping for myself. ;o)

Except that their problem is that they fail also to attach value to the time they take in making a decision. When I was effectively paid by the hour, that was easier to calculate because it gave me a monetary figure which could then be factored into the preliminary calculations...

I've recently started working through chunks of Deuteronomy (again), with the help of Gordon McConville's excellent commentary on the book, which seems to be very difficult to get hold of. I had it on order from the publisher for 6 months, gave up, the first two attempts at buying it via Amazon sellers didn't work (they didn't have it, but thought they did), but I eventually got a copy.

It's amazing how badly we can misunderstand common passages simply because preachers don't check their facts. For example, the First Commandment (Protestant numbering) of the 10 says

You shall have no other gods before me.

The standard sermon on that tends to go down the line of saying that God should be our number 1, or something. McConville helpfully points out that "before me" is literally "before my face" and is primarily spatial - it's saying that we shouldn't have any other gods at all in God's presence, rather than just being a weak statement about priorities.

Does that affect most of the sermons I have heard on the topic? No.

Calvin gets it right, in his excellent exposition of the 10 Commandments, though he wasn't working from the English translation...

Here's the audio of my sermon from last night. Let me know if it doesn't work.

Or you can download it from here.

Here's the rough text. I'll try to put the audio on tomorrow...

If our lives are less than we want, it is most likely either because we do not see Jesus clearly enough or because we ignore what we do see of him.

If our lives are less than we want, it is most likely either because we do not see Jesus clearly enough or because we ignore what we do see of him.

Let us pray....

This might come as a surprise to you, and it would certainly come as a surprise to some of my lecturers, but the Psalms weren't just stuck together randomly, which is one of the reasons it's such a good idea to work through them in order. We're in Psalm 21 tonight, which is part of a big group of Psalms which are about God's king – David. That's why it says at the top “A Psalm of David”. It won't surprise you to know that Psalm 21 comes just after Psalm 20, and just before Psalm 22. That might sound like the most stupidly, mind-numbingly obvious thing you've ever heard, but it's important and it's easy to miss. We'll come back to it.

So this is a Psalm about God's king, David, and by the looks of it, it's about David just after a battle.

O Lord, the king rejoices in your strength. How great is his joy in the victories you give.

There's loads of stuff in this Psalm we could look at, but we're just going to focus on two things tonight. First, God's king wins because he prays. God's king wins because he prays. Maybe you noticed that. Verses 1-2

O Lord, the king rejoices in your strength. How great is his joy in the victories you give! You have granted him the desire of his heart, and have not withheld the request of his lips.

God's king wins because he prays. He doesn't win because he has the best army, though 1 Chronicles goes on and on about what an impressive army David had. He doesn't win because of his superior wisdom or tactics. He doesn't win because his enemies are weak or stupid. God's king wins because he prays, and because God gives him the victory.

I said that Psalm 21 comes after Psalm 20. Last week, you looked at Psalm 20, and it is obviously set just before a battle.

Psalm 20:4 May he give you the desire of your heart and make all your plans succeed. We will shout for joy when you are victorious, and will lift up our banners in the name of our God. May the Lord grant all your requests. Now I know that the Lord saves his anointed – that's the king again – he answers him from his holy heaven with the saving power of his right hand. Some trust in chariots and some in horses, but we trust in the name of the LORD our God.

Psalm 20 is before the battle. Psalm 21 is afterwards. In 20:4 they pray that God would give the king the desire of his heart. In 21:2 God has given it to him. In 20:7 they are saying they will stand firm because they trust in the name of the LORD. In 21:7, the king has stood firm because he trusts in the LORD. God's king wins because he prays.

Now I could try to apply this to us, and say that if we pray, we will win. But it's not that simple. We aren't God's king, so we can't just rip this passage out of context and say straight away that it applies to us.

But Jesus is God's king, and this passage is about him.

Something I find really striking about prayer is Jesus and Peter in the garden of Gethsemane. Flick to Mark 14 if you want – we're not going to be there long.

It's the night before Jesus dies. He knows he is going to be betrayed and arrested and killed, and he tells the disciples. Peter says to him v31 “even if I have to die with you, I will never disown you”. Then Jesus goes to Gethsemane and prays. Peter goes with him, but he can't stay awake. Jesus says v38 “watch and pray so that you will not fall into temptation. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” Peter falls asleep again Jesus gets arrested. Peter follows him. Jesus keeps going through his trial and execution. Peter doesn't. Peter denies he even knows Jesus. Jesus prayed. Jesus kept going. Peter didn't pray. Peter dropped out. God's king wins because he prays.

But we don't just see it there. The Resurrection happened because Jesus prayed. Hebrews 5:7 – you don't need to turn to it.

During the days of Jesus' life on earth, he offered up prayers and petitions with loud cries and tears to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission.

The resurrection happened because Jesus prayed. God's king wins because he prays. And you know what? That is a great reason for us to be encouraged. Jesus prays. Jesus wins because he prays. God gives him victory. God gives him the desire of his heart and does not withhold the request of his lips. And do you know what Jesus is praying for right now?

Us.

Romans 8, from v31.

What, then, shall we say in response to this? If God is for us, who can be against us? He who did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all – how will he not also, along with him, graciously give us all things? Who will bring any charge against those whom God has chosen? It is God who justifies. Who is he that condemns? Christ Jesus, who died – more than that, who was raised to life – is at the right hand of God and is also interceding for us. Jesus is praying for us. He is praying that those who trust in him will not be condemned, that we will be forgiven and that we will not be separated from his love.

It has been a great encouragement to me over this last year to have some of you folks praying for me. I know the week or so after I send out a prayer letter, I am always hugely encouraged and really want to know God much more.

But how much more of an encouragement should it be to me that Jesus Christ, God's anointed king over the whole universe, that Jesus Christ is praying for me. And God's king wins, because he prays.

If you are a Christian here tonight, be very encouraged because Jesus Christ is praying for you. It doesn't matter what situation you are in, or how bad things are. Jesus is still praying for you, and Jesus wins because he prays.

Of course, if Jesus wins because he prays, that is really challenging to me because I don't pray anywhere near enough. And prayer is one of those things it's really easy to get into an unhealthy guilt trip about, so I'm not going to spend a lot of time on it; I'm just going to share with you something that happened to me the other day. It was the week after I'd sent out my prayer letter, so this isn't to my credit at all. This is because you guys were praying for me. It was about 10 o'clock at night. I was in bed, and I wasn't feeling very tired. And I was reminded of how important prayer is, and I was starting to think about this sermon, so I decided to pray for a bit. To start with I aimed for 11pm, but I ended up going on past midnight. I prayed through the passage, through difficult issues in my life, for friends who I knew were having a hard time. And that night was so encouraging, and helped me so much, but I'm so rubbish at getting down to prayer that I haven't done that again since.

If we want to spend time in prayer, we need to make time for prayer. I don't know what your prayer lives are like – I imagine some of you are much better at it than me, and some of you are still learning. But why don't we all agree, between us and God, and if you've got an accountability partner or a husband or wife or something, agree with them too to spend more time in prayer. Lets all agree to set aside more time every day for prayer. Maybe first thing in the morning or last thing at night, because those don't tend to get pushed as much. Maybe during the lunch break. Maybe agreeing to spend an hour a week in prayer with a friend. Maybe making sure you pray through your day before checking your e-mail in the morning. When I was in 6th form, I quit my morning paper round because it was making me too tired, but that time was great for reading the Bible and praying. But whatever it is, we desperately need to pray more, so set aside time to do it.

God's king wins because he prays. So we should be confident because God's king Jesus is praying for us and we should pray because prayer matters.

Secondly, God's king wins, so he rejoices.

O Lord, the king rejoices in your strength. How great is his joy in the victories you give. You have granted him the desire of his heart and have not withheld the request of his lips. You welcomed him with rich blessings, and placed a crown of pure gold upon his head. He asked you for life and you gave it to him – length of days for ever and ever. Through the victories you gave, his glory is great; you have bestowed on him splendour and majesty. Surely you have granted him eternal blessings and made him glad with the joy of your presence.

I don't know about you, but the way I think of Jesus is often messed up. I think of him as a guy who walked around Israel healing people and teaching, which he was, or as God who died on the cross for my sins, then rose again, which is true because he is. Or as the one who is in heaven, praying for me and so I can come into God's presence and speak to God. And that's amazing, and that's true.

But when I think of Jesus, I tend to think of him as a man of sorrows, which he was. I don't think of him as rejoicing. I was chatting about this to a friend the other day, and she said that Jesus is the happiest guy she knows. Isn't that striking? Right now, Jesus is rejoicing in the victory he has won, the victory over sin and over death and over the devil, the victory that is being worked out in our lives and that means if we trust Jesus, we will be in glory with him. Listen to Hebrews 12:2.

Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy set before him endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God.

Jesus went through the cross because of the joy set before him. It's like if you know there's a really exciting ride at a theme park, it's worth queuing for. If there's a really nice place to go on holiday, it's worth being stuck on a plane with your face in someone else's armpit and a baby vomiting all over you for a few hours to get there. It's like with Jacob and Rachel in Genesis. Genesis 29:20

So Jacob served 7 years to get Rachel, but they seemed like only a few days to him, because of his love for her.

It's like that with Jesus – because he knew how much joy there was in the victory, he was willing to go through the cross to get there.

Right now, Jesus is rejoicing in the victory he has won. He doesn't mind what it cost – it is worth it. And what it cost him was betrayal, humiliation, shame, suffering and dying a horrible death under God's judgement.

We're looking at Psalm 21. Psalm 20 – God's king prays for victory. Psalm 21 – God's king rejoices in the victory. Psalm 22 – the Psalm Jesus quoted as he was dying – God's king dies on the way to victory.

But what makes this victory so joyful? Lets look at Psalm 21 in more detail.

verse 1 – the king rejoices in God's strength, and in the victory he gives. Verse 2 because God answers prayer. Verse 3 because God welcomes the king and places a crown of pure gold on his head – that's a symbol of victory here. Verse 4 – more answered prayer. Verse 5 – victory, glory, splendour, majesty.

Verse 6.

Surely you have granted him eternal blessings and made him glad with the joy of your presence.

The key factor in all this joy is that it is the joy of God's presence. It is the joy not just of knowing about God – that God is strong, that God is victorious, not just the joy of knowing God, but of being with God. It is the joy of being welcomed by God, the creator of the universe, the one who alone gives the victory, the mighty God over everything. Imagine the most amazing, the most wonderful person you possibly can, and they don't even come close If you're in love with someone, you really enjoy spending time with them. But God is far more wonderful than anyone you have ever loved.

Being welcomed by him, knowing the joy of his presence, enjoying being with God. That is the joy that was set before David here. That was the joy that was set before Jesus, but not just the joy of him being with God, because he had that from the beginning, but the joy of us sharing in being with God and rejoicing in God too.

God's king wins, so he rejoices.

So if Jesus went through humiliation, through suffering and through death because of this amazing joy that was set before him, if right now he is rejoicing in being with God and because we can be with God too and we can share in his joy and in his victory, that raises one big question in my mind.

Why on earth are we so miserable?

I mean, I'm not saying we should always walk around with plastic smiles on our faces or something. And yes, things go wrong, and yes, Jesus has gone through suffering and death to glory and joy, but we're following and in a sense we're not there yet because we've still got suffering and we've still got to die and although we can see the end, there's still a bit of a way to go, but why aren't we excited about it?

Little kids are great, because they are useless at hiding what they feel. You see a kid about to go on a ride they are really looking forwards to, and they're jumping all over the place and they're really excited, and they can't stop talking about it or asking “are we nearly there yet”. Why aren't we like that?

As far as I can see, either it is because we aren't that excited at the greatest news that anyone has ever heard or because we've got very good at hiding it. And both of those alternatives are pointless and stupid, and I think with most of us it's a bit of both. So spend time thinking about how amazing God's victory is, how amazing God is and how wonderful it is that we can be with him. Spend time enjoying God's presence. And don't be embarrassed about being excited about what God has done. Look, if there is anything in the whole history of the entire universe that is worth getting excited about, it is this. (I give you permission to get excited about being with God.)

I mean – what could be better? God, the most amazing person in the whole universe, has made it so that we can be with him. It's much better than meeting your favourite celebrity, or even getting to know them as a friend or live with them. This is God we're talking about here!

When I lived round here, I used to go to the monthly church prayer meetings. And they are really important, and it was great that the numbers kept on going up, and there was loads that was good about them.

There was one thing that always upset me though, and that was how little time we actually spent praying. If we had 30 minutes to pray about a topic, someone would stand up and speak for 20 minutes and then we'd pray for 10 minutes, which I always thought suggested that they liked hearing the sound of their own voice twice as much as they liked praying to God.

But looking back, I was wrong. What should have upset me more was that when we just had a time where we weren't told what to pray for except to praise God, that so few people prayed. We saw praying to God for stuff as more important than rejoicing in who God is and what he has done. And sometimes, yes, we can be so overwhelmed with stuff in our minds that we need to commit it to God first.

But surely rejoicing in who God is and what he has done is the main point. I mean, if God is the kind of trustworthy God it's worth praying to, and he is, then surely he's worth praising too! And it is when we spend time praising God and rejoicing in his presence and telling others how amazing he is that our attitudes are right so that we pray properly.

Look at the people in the Psalm – not the king, the normal people, the people singing it. Actually, their situation is a lot like ours. They aren't there yet either. They still have a whole load of enemies to deal with. Just look at verses 8-12.

But they're still praising God. They're singing this Psalm. How do they react to these enemies? They pray to God about them, and they don't worry about them at all. They know God has got it sorted.

Your hand will lay hold on all your enemies, your right hand will seize your foes. At the time of your appearing, you will make them like a firey furnace. In his wrath, the Lord will swallow them up, and his fire will consume them. You will destroy their descendants from the earth, their posterity from mankind. Though they plot evil against you, and devise wicked schemes, they cannot succeed; for you will make them turn their backs when you aim at them with drawn bow.

These people have seen God's victory. They have seen that God's king wins, so they don't worry about the future.

What do they do? They sing and praise God's might. They rejoice.

God's king wins, so God's people trust him, we pray to him and we rejoice in him.

I've been to quite a few services at St Mary's over the years. And they mostly end the same way. There's a final hymn, we say a short prayer, the guy who led and the preacher walk over to that door. Then some people, usually the people who are here because they're getting married soon or something, try to make a quick exit before anyone talks to them. We're not actually that scary, you know! Everyone else stays really quiet for about a minute, then starts chatting to someone sitting near them about football, or the week, or the weather, or exam results, or something like that. It's a lot better than some of the churches I've been to, where people just chat to people they already know well, because then it's really hard to feel like anything except an outsider. But that's not how I want us to do it tonight, because it's really easy if God's been speaking to you or challenging you just to forget about it and not let it affect your life. So what I'm going to suggest is that at the end of the service, if you've got to leave in a hurry, that's fine. But I guess that some people here tonight feel that God has been speaking to them. Maybe you're not a Christian, and you've realised that actually if Christianity is that exciting, you'd like to do something about it. Maybe you are a Christian and God has been challenging you about something in your life, and you know that you don't want to let it go without changing. Maybe you've been reminded of what an awesome God we serve, of what he has done for us, and you just want to praise God and recommit yourself to follow him. If that's you - I'd like you to pray about it with someone, or get them to pray for you. It could be your husband or your wife, it could be a good friend who's a Christian, it could be me or one of the prayer team who are going to be over there after the service. We're happy to pray for anyone who wants praying for.

So if you're wanting to catch up with a friend after the service, ask if you can pray for them first, because it might be that God has been really challenging them and they need someone to pray with. If you don't want to pray with anyone, that's fine too, but I'd ask that you give people who do want to pray the space to do that before you grab them to chat about the footie. God's king wins, because he prays. David won because he prayed. Jesus kept going through suffering and death because he prayed. Jesus rose from the dead because he prayed. Now he is praying for us, so we can be very confident in God, and we can see something of how important prayer is.

God's king wins, so he rejoices. He rejoices in God's presence, in how amazing God is, and because we can share in God's presence and in his joy too. Shouldn't we rejoice and praise God?

Lets just have a short time of silence, then I'll pray and we'll do some rejoicing and praising God by singing our final hymn...

In their own day, the prophets were headline makers and pacesetters in the national news, so if we find their ways tedious, unclear, less than exciting, the fault does not lie with them.

Alec Motyer, quoted by Greg Haslam in Preach the Word

There's a verse in 1 Corinthians which tells us a bit about how to understand the Bible. It is interesting that what it says actually goes against at least two commonly held beliefs by some people who teach theology and stuff. Of course, there are about as many opinions as there are theologians...

Now these things happened to them as an example, but they were written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come.

1 Corinthians 10:11, ESV

"These things" refers back to what Paul has just been writing about - specifically details of the Exodus and the Israelites wandering in the desert that had happened over a thousand years before. There is a tendency in liberal theological circles, thankfully starting to die out now, to say that if something has theological value, it doesn't also have historical value. So people argue that because Jesus turning water into wine is a picture of him replacing the temple (which it is), that means it didn't happen, because the theological point is a good enough reason to record the story.

That is of course complete rubbish, because the theological truths also need to have a correspondence to reality. If Jesus did not rise bodily from the dead, then the "theological point" that is made by the accounts of his resurrection is false. In order for the theology to be valid, the history needs to be valid as well. (Yes, there's a whole load of stupid arguments among some German scholars ages ago about what the meaning of history is. They are stupid. I'm using "history" in the sense of "events that really happened in the past".) That's a point that has been well made in a lot of the New Testament stuff by NT Wright, and others.

Paul's point here is that the events of the Exodus took place as examples. They took place. And they did so as examples - both the theological and historical are true, and indeed need to be true in order for them to be valid examples. Yes, there are cases (Jesus' parables for instance) where things do not have to be true in order for them to be valid examples. That isn't the case here.

One of the most commonly taught ideas in the whole area of how to understand the Bible is the idea of the importance of original context and original meaning. The main meaning of a passage is what it meant for its original recipients.

The problem is that what Paul says contradicts it. It doesn't contradict the idea that original context is often very important for understanding the passage, or that the original significance for the readers is important. But Paul says that the events recorded in Exodus happened and were recorded "for us". Why? Because the "end of the ages" has come - which in Paul's theology refers to the fact that Jesus has come - that all the ages were pointing to what happened in Jesus. Paul sees the main significance of the events of the Exodus as being for people living after Jesus, because he sees them as being fulfilled in Christ. That of course clashes with the conventional view (in many circles) of how to understand the Bible. The main significance of the passage is found in Jesus and for those who seek to follow him. It doesn't bother Paul that it was originally written 1000 years before the events that give it its main meaning.

Peter also agrees that the main significance of passages in the Old Testament wasn't understood until Jesus. Furthermore, he even argues that the writers knew that they didn't fully understand.

Concerning this salvation, the prophets who prophesied about the grace that was to be yours searched and inquired carefully, inquiring what person or time the Spirit of Christ in them was indicating when he predicted the sufferings of Christ and the subsequent glories. It was revealed to them that they were serving not themselves but you, in the things that have now been announced to you through those who preached the good news to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven, things into which angels long to look.

1 Peter 2:10-12, ESV

I therefore conclude that the main significance of a Bible passage is the one that takes into account the original context and significance, but which points through them to Jesus. To my mind, if an Old Testament commentary doesn't do that, it is missing the main point.

1) The main purpose of studying any text is to explain who wrote it. In comparison, everything else is hardly worth bothering with.

2) No text has only one author.

3) It is obvious that texts always originate within a group where the view described by the text is already dominant. Hence texts advocating monogamy, for example, can only originate in monogamous societies. Texts describe people's opinions. They do not change them.

4) Events described in a text only rarely actually happened. More often, they are a well-understood metaphor for a view held by the group (or one of the groups) that wrote the text.

5) No group of writers can produce more than one literary style.

6) If similar events are described twice, it is clearly the same event as put forwards by different authors. For example, in the proto-myth underlying Four Weddings and a Funeral, there can only have been one ceremony, which has been described by a wide variety of different authors. Five redactors, R1, R2, R3, R4 and R5 then compiled their own versions of the story from different limited selections of sources, one of them as an ironic reaction against the proto-myth. These five tales were then deemed sufficiently different by another redactor, RF that they were placed side by side instead of synthesised into a common whole. Hence the confusion.

7) Don't take two much notice of the approaches used by other disciplines; they are clearly ignorant. For example, many modern textbooks in the pseudo-academic discipline of History claim that there were two "World Wars" in the first half of the 20th century with Britain, the USA, France and Russia on one side and Germany, Austria and so on on the other. This is of course patently absurd - a much simpler explanation is clearly that there was only one war. An even more absurd example is the multiplication in the history books of "Gulf Wars" between US President George Bush and Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussain. How can the same war have happened twice in such a short space of time? And no-one really believes that there are two Presidents called George Bush and George W Bush - it is much more likely that they were originally two descriptions of the same president, and a later redactor got confused.

8) The context of a verse in the present text does not matter. What matters is its context in the text in which it was originally set. The fact that no two scholars can agree precisely on this should not affect your level of confidence in your own views.

9) None of these rules applies to this text.I really like the title of one of Richard Feynman's autobiographies - "What do you care what other people think?". His wife Arlene said it to him at one point, and it had a transformative effect on his life.

I used to think that being concerned about what other people think about you was wrong. I've changed my mind, because what other people think about you affects your communication to them and your relationships with them, and that matters.

On the other hand, I think what I meant, even though I didn't understand it clearly, is that we shouldn't fear other people compared to our attitude to God. We shouldn't try to avoid displeasing others at the expense of displeasing God. We should be far far more concerned about what God thinks of our actions than what others think.

On a more humourous note, I came across this quotation the other day, but have slightly changed the wording in my head so have no idea who said it originally.

The key to not worrying about what other people think about you is to realise that by and large they don't.

According to the BBC, food packagers are making stated portion sizes on the "Nutritional Information" panel too small to make it look like their foods aren't as fatty and salty as they really are. The example they gave was a stated portion size of one 15g chicken nugget.

I don't eat chicken nuggets often, but my real problem with this is cereal. Yes, maybe I do eat a bit too much sometimes, but I figure a decent amount of cereal to eat for breakfast (when I have it) is a decent-sized bowlful, which is also about enough that I can work until lunchtime without getting all hypoglycemic all over the place. I don't usually buy cereal in the holidays, and the other day I remembered why. A friend had asked me to finish up some milk for them, so I bought a box of Jordan's. Really nice, but the boxes only seem to hold 3 bowls of cereal each. That means that if a family of 4 were eating it, you'd average over 9 boxes a week, at a cost of nearly £30. For breakfast cereal. It's nice, but it's not that nice.

Just randomly surfing the internet avoiding going to bed, and I observed that the official homepage of the Zimbabwean government looks as if it was put together by a primary school class using a 1990s WYSIWYG editor. It's sad when a country is so obviously being trashed by its leaders and yet it still pretends everything is ok and going well, but they can't even afford a half-competent teenager to do their national webpage.

If our lives are less than we want, it is most likely either because we do not see Jesus clearly enough, or because we ignore what we do see of him.

One of my Edinburgh correspondents pointed out this excellent video...

I'm still working my way through Dale Ralph Davis's excellent series of books on Joshua - 2 Kings. I've rationed myself to one chapter per day so that I actually get space to think about stuff. Often he'll just put a paragraph in on an idea, and actually someone could take that idea and spin it off and write a book about it or something. This is, I think, one of those ideas.

The friendship between David and Jonathan in 1 Samuel is a remarkable one. Jonathan is the heroic and godly heir to the throne - his father Saul is king. But Saul is a bad king - largely because (unlike Jonathan) he never really got the idea of trusting God. So God has said that Saul's family will lose the kingship, and it will pass instead to David. Not surprisingly, Saul doesn't like the idea and spends a lot of his time trying to get rid of David.

Jonathan, then, is in an interesting position. On one hand, he is eminently suitable for the kingship. He is the eldest son of the king; he has just the sort of character one would want in a king. But David is God's anointed (which is the key idea in Samuel). How will Jonathan respond? Will he seek to be king himself, or will he submit himself to God's anointed king at the cost of being king himself?

In a lot of ways, this is a similar situation to ours. We might well appear to be capable of running our own lives. We might even be good at it. We have, it seems, every right to be king. But God has said that we cannot be the rightful kings of our own lives. We need to submit to another - to God's anointed - to Jesus.

We see this clearly in 1 Samuel 20, which is where it all comes to a head.

Saul's anger flared up at Jonathan and he said to him, "You son of a perverse and rebellious woman! Don't I know that you have sided with the son of Jesse [i.e. David] to your own shame and to the shame of the mother who bore you? As long as the son of Jesse lives on this earth, neither you nor your kingdom will be established. Now send and bring him to me, for he must die!"

1 Samuel 20:30-31, NIV

Saul is desperate to keep the kingship. He ends up losing it and his life. Jonathan is willing to give up his kingship to David, and after he dies, his disabled son ends up eating at the king's table.

Every single time in my life I have personally known details of a news story, the media have got some basic facts wrong. Every single time, including stuff which made the headlines on Sky, BBC, stuff near the front of major national newspapers, etc. Except, of course, the ones where they were so lazy they just repeated a press release pretty much verbatim. Some of them have been true.

To be fair to them, despite their massive biases in some areas, the BBC at least ask people involved to check the facts.

An example recently is quite funny. A few weeks ago, a man called Oli Young started a group on Facebook called "If 100,000 people join this group, my wife will let me name my second child Spiderpig". Such things are fairly common on Facebook, but for some reason this one took off. It was reported on lots of different news networks, including the Times and Sky News.

The problem was that this one was a joke - there was no child and no intention of naming them Spiderpig. It even said that on the website linked to prominently from the Facebook group, and Mr Young told anyone who asked that it was a joke.

Oli Young writes:

I also learnt about the gullibility and laziness of main stream media when it comes to "teh internets". Neither The Metro, Sky News nor any other media orgs that went to press with this "story" actually talked with me, they took it at face value and made somewhat fools of themselves with it. Other orgs did contact me, including the BBC. I felt it necessary to tell them the truth, and once they knew it, they knew there was no story. My entire life is but one google away, it's not that hard to find out about me. I've also turned down paid interviews for "major womens magazines".

I don't know why he thinks this laziness and gullibility is connected to the fact it's the Internet though. Just look at the whole Wycliffe saga. Or any of the other news stories I've known people involved with...

I should probably add that as far as I am aware, Ruth Gledhill is the only responsible religion journalist working for a national newspaper. She at least makes an effort to find out what is going on.

I'm spending more time than I used to with people on both sides of the conservative / charismatic evangelical distinction. I used to spend time mainly with people on the conservative side. And I call it a distinction rather than a divide because I don't think they especially are divided. And the more time I spend, the more I realise that the issue isn't Word v Spirit - both sides (at their best) agree that Word and Spirit work together on both sides. (Of course, there are non-evangelical charismatics, who don't bother with the Word, but I'm talking about the evangelical ones).

I think the distinction is the tension between discernment and passion. Conservatives tend to stress discernment more; charismatics passion. At their worst, the conservatives get too discerning and not at all passionate. At the charismatics' worst, they get really passionate, but with no discernment for truth.

A good church and a mature Christian should exhibit both a burning passion for God, and discernment over what is true and what is false.

My general impression is that most of our services are terribly depressing. I'm amazed that people still go to church. Most who go are female and over the age of forty. The note missing is this joy in the Holy Ghost. There is nothing in these services to make a stranger feel he is missing something by not being there. The main trouble with evangelicalism today is its lack of power. What do our people know of joy in the Holy Ghost? Without this joy in the Holy Ghost the situation in this country is hopeless.

Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, cited in Greg Haslam, Preach the Word

When evangelicals call the Bible "inerrant," part at least of their meaning is this: that, in exegesis and exposition of Scripture and in building up our biblical theology from the fruits of our Bible study, we may not (1) deny, disregard, or arbitrarily relativize, anything that the biblical writers teach, nor (2) discount any of the practical implications for worship and service that their teaching carries, nor (3) cut the knot of any problem of Bible harmony, factual or theological, by allowing ourselves to assume that the inspired writers were not necessarily consistent either with themselves or with each other. It is because the word "inerrant" makes these methodological points about handling the Bible, ruling out in advance the use of mental procedures that can only lead to reduced and distorted versions of Christianity, that it is so valuable and, I think, so much valued by those who embrace it.

James I. Packer

(hat tip to CQOD)

Helpful quote, but I disagree. The word "inerrant" does not make those methodological points. The theological baggage attached by some to that word leads to those (correct) conclusions though.

Intro | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

link to full text of statement

Overall, it was stronger than I expected it to be. By pointing to Jesus' doctrine of Scripture and affirming that hermeneutics should be centred on Christ, they effectively secured an evangelical approach to the Old Testament.

On the other hand, it still seems to have weaknesses, particularly in the question of genre. I don't remember anything guaranteeing a belief in the essential historicity of the gospel accounts, for example, rather than the view which sees them as intentionally written to be legendary accounts pointing to a spiritual truth. There are also a few areas where the wording seems to be less than ideal. It seems to me curious but true that it puts more effort into safeguarding and emphasising the teaching of Jesus as recorded in the Bible than his historical death and resurrection, which is where the emphasis of the Bible itself seems to be more focused. Possibly that is because while the underlying doctrine has been held by the Church since the beginning, this expression of it is reacting against certain false teachers, and so faces the danger of over-reacting.

Some of my initial thoughts were wrong, because I had not realised that "inerrancy" is often used as jargon to carry a lot more meaning than the word "inerrant" on its own does. But it still does not carry quite enough weight, and the use of one word to carry meanings not entirely stemming from that word is potentially confusing.

Intro | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

link to full text of statement

The Statement ends with a prose "Exposition". Here are some edited highlights.

The theological reality of inspiration in the producing of Biblical documents corresponds to that of spoken prophecies: although the human writers' personalities were expressed in what they wrote, the words were divinely constituted. Thus, what Scripture says, God says; its authority is His authority, for He is its ultimate Author, having given it through the minds and words of chosen and prepared men who in freedom and faithfulness "spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit" (1 Pet. 1:21). Holy Scripture must be acknowledged as the Word of God by virtue of its divine origin...

Jesus Christ, the Son of God who is the Word made flesh, our Prophet, Priest, and King, is the ultimate Mediator of God's communication to man, as He is of all God's gifts of grace. The revelation He gave was more than verbal; He revealed the Father by His presence and His deeds as well. Yet His words were crucially important; for He was God, He spoke from the Father, and His words will judge all men at the last day.

As the prophesied Messiah, Jesus Christ is the central theme of Scripture. The Old Testament looked ahead to Him; the New Testament looks back to His first coming and on to His second. Canonical Scripture is the divinely inspired and therefore normative witness to Christ. No hermeneutic, therefore, of which the historical Christ is not the focal point is acceptable. Holy Scripture must be treated as what it essentially is—the witness of the Father to the Incarnate Son....

Mostly great so far. Slight irony in saying "Yet His words were crucially important" though - I thought his death was the crucially important bit of his revelation. Certainly Scripture seems to point at least as much to God as revealed particularly in Christ's death and resurrection as in his teaching. Yes, Jesus came to teach; he also came to die.

The New Testament canon is likewise now closed inasmuch as no new apostolic witness to the historical Christ can now be borne. No new revelation (as distinct from Spirit-given understanding of existing revelation) will be given until Christ comes again. The canon was created in principle by divine inspiration. The Church's part was to discern the canon which God had created, not to devise one of its own.

Logical error here. Yes, no new apostolic witness to the historical Christ can now be borne. But it does not therefore follow that no new revelation will be given until Christ comes again. No new normative, authoritative revelation - yes. But no new revelation at all - not proven.

By authenticating each other's authority, Christ and Scripture coalesce into a single fount of authority. The Biblically-interpreted Christ and the Christ-centered, Christ-proclaiming Bible are from this standpoint one. As from the fact of inspiration we infer that what Scripture says, God says, so from the revealed relation between Jesus Christ and Scripture we may equally declare that what Scripture says, Christ says.

Skirting close to, but this time just avoiding the danger of Bibliolatry (avoiding because of the phrase "from this standpoint"). But it's right that what Scripture says, Christ says.

We affirm that canonical Scripture should always be interpreted on the basis that it is infallible and inerrant. However, in determining what the God-taught writer is asserting in each passage, we must pay the most careful attention to its claims and character as a human production. In inspiration, God utilized the culture and conventions of His penman's milieu, a milieu that God controls in His sovereign providence; it is misinterpretation to imagine otherwise.

So history must be treated as history, poetry as poetry, hyperbole and metaphor as hyperbole and metaphor, generalization and approximation as what they are, and so forth. Differences between literary conventions in Bible times and in ours must also be observed: since, for instance, non-chronological narration and imprecise citation were conventional and acceptable and violated no expectations in those days, we must not regard these things as faults when we find them in Bible writers. When total precision of a particular kind was not expected nor aimed at, it is no error not to have achieved it. Scripture is inerrant, not in the sense of being absolutely precise by modern standards, but in the sense of making good its claims and achieving that measure of focused truth at which its authors aimed.

So what Scripture affirms is now "that measure of focused truth at which its authors aimed". If the aim of Genesis 1-2 was not to teach about science, how does that fit with the earlier comments about creation? It still is not clear how we are meant to tell what is meant to be hyperbole and metaphor, and what isn't.

Apparent inconsistencies should not be ignored. Solution of them, where this can be convincingly achieved, will encourage our faith, and where for the present no convincing solution is at hand we shall significantly honor God by trusting His assurance that His Word is true, despite these appearances, and by maintaining our confidence that one day they will be seen to have been illusions.

I agree. :o)

We are conscious too that great and grave confusion results from ceasing to maintain the total truth of the Bible whose authority one professes to acknowledge. The result of taking this step is that the Bible which God gave loses its authority, and what has authority instead is a Bible reduced in content according to the demands of one's critical reasonings and in principle reducible still further once one has started. This means that at bottom independent reason now has authority, as opposed to Scriptural teaching. If this is not seen and if for the time being basic evangelical doctrines are still held, persons denying the full truth of Scripture may claim an evangelical identity while methodologically they have moved away from the evangelical principle of knowledge to an unstable subjectivism, and will find it hard not to move further.

Yes. But I think that the Statement does not quite stop that as much as it intended to.

Intro | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

link to full text of statement

The remaining Articles 14-19 are, as far as I can see, much better.

ARTICLE 15:

WE AFFIRM that the doctrine of inerrancy is grounded in the teaching of the Bible about inspiration.

WE DENY that Jesus' teaching about Scripture may be dismissed by appeals to accommodation or to any natural limitation of His humanity.

Saying that Jesus' teaching about Scripture cannot be dismissed by those appeals solves the problem for much of the Old Testament, because it is clear that Jesus regarded it as historical rather than as collective myth or any of the other rubbish that some scholars claim.

ARTICLE 16:

WE AFFIRM that the doctrine of inerrancy has been integral to the Church's faith throughout its history.

WE DENY that inerrancy is a doctrine invented by scholastic Protestantism, or is a reactionary position postulated in response to negative higher criticism.

Need to be careful here. The doctrine underlying inerrancy - what they are trying to express about the trustworthiness of Scripture has indeed been integral to the Church's faith. Patristic writers in the early church, Reformers, Counter-Reformers all cited the Bible as true and authoritative. On the other hand, the articulation of it as "inerrancy" does seem to be invented by scholastic Protestantism in reaction to negative higher criticism, and there are some consequences of that. One example is that there does not seem to have been a move to treat 144 hour creation as a confessional point until Darwin. Indeed, many of the early Church Fathers (e.g. Augustine) argued that creation did not take place over a 144 hour period, but that the term "day" in Genesis 1 referred to longer periods. 144-hour creation as confessional probably does owe something to the newness of the specific articulation of the doctrine of inerrancy, even though the underlying doctrine goes back right to the beginning of Christianity.

ARTICLE 18:

WE AFFIRM that the text of Scripture is to be interpreted by grammatico-historical exegesis, taking account of its literary forms and devices, and that Scripture is to interpret Scripture.

WE DENY the legitimacy of any treatment of the text or quest for sources lying behind it that leads to relativizing, dehistoricizing, or discounting its teaching, or rejecting its claims to authorship.

This is also a useful clarification. Although there is still room for a liberal view of some bits of Scripture via claiming (for example) that John's gospel is metaphorical midrash rather than history, this rules out the potential genre of pseudographia - some claim that someone who had known Peter writing later as Peter was a well-understood literary convention. This rejects that for Biblical books (and rightly so, given the second century Church's attitude to pseudographia).

Intro | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

link to full text of statement

Articles 11-13 are the heart of the document.

ARTICLE 11:

WE AFFIRM that Scripture, having been given by divine inspiration, is infallible, so that, far from misleading us, it is true and reliable in all the matters it addresses.

WE DENY that it is possible for the Bible to be at the same time infallible and errant in its assertions. Infallibility and inerrancy may be distinguished, but not separated.ARTICLE 12: WE AFFIRM that Scripture in its entirety is inerrant, being free from all falsehood, fraud, or deceit.

WE DENY that Biblical infallibility and inerrancy are limited to spiritual, religious, or redemptive themes, exclusive of assertions in the fields of history and science. We further deny that scientific hypotheses about earth history may properly be used to overturn the teaching of Scripture on creation and the flood.ARTICLE 13: WE AFFIRM the propriety of using inerrancy as a theological term with reference to the complete truthfulness of Scripture.

WE DENY that it is proper to evaluate Scripture according to standards of truth and error that are alien to its usage or purpose. We further deny that inerrancy is negated by Biblical phenomena such as a lack of modern technical precision, irregularities of grammar or spelling, observational descriptions of nature, the reporting of falsehoods, the use of hyperbole and round numbers, the topical arrangement of material, variant selections of material in parallel accounts, or the use of free citations.

This is also where I think the statement gets too fuzzy. Article 11 says that the Bible is "far from misleading us, it is true and reliable in all the matters it addresses". Scripture cannot mislead, but people can misunderstand it and so be misled. There is also the key question of how it is determined which matters it addresses.

How, for example, do these articles relate to poetry such Psalm 19:4-6?

In the heavens [God] has pitched a tent for the sun,

which is like a bridegroom coming forth from his pavilion,

like a champion rejoicing to run his course.

It rises at one end of the heavens

and makes its circuit to the other;

nothing is hidden from its heat.

Psalm 19:4b-6, NIV

Yes, I can accept that it is poetry and so we do not take God having pitched a tent for the sun literally. But how can we on the one hand say that is poetry so we don't have to take it literally and on the other say that the accounts of the bodily resurrection of Jesus from the dead are historical rather than pious unhistorical myth teaching a spiritual truth (as some argue)? Who is to classify the genre of literature? Yes, I believe Jesus rose bodily from the dead. But I don't think even with this statement's expanded use of the term "inerrancy", that it can do the work it is meant to do. It seems to me possible to agree with this statement and yet deny key doctrines it is meant to be defending.

Article 12 says "We further deny that scientific hypotheses about earth history may properly be used to overturn the teaching of Scripture on creation and the flood." Quite right. What Scripture teaches is correct. The Statement does however allow scientific hypotheses about earth history to clarify the interpretation of the teaching of Scripture on creation and the flood, which is quite possibly something some of the people who wrote it would also disagree with.

Article 13 says "WE AFFIRM the propriety of using inerrancy as a theological term with reference to the complete truthfulness of Scripture." Once again, I am uncertain what it means for a poem employing metaphor to be truthful. Or a love song, for that matter.

I rather imagine that the second half of Article 13 is meant to deal with this problem. But if it allows for hyperbole (which it should), how can we contradict those who argue that the description of Jesus walking on water was just hyperbole?

Part 5 | Part 6 | SummaryNice to know there are people out there who agree with me about New Wine. I've never been to the festival, but know a lot of people involved.

If you feel safe and secure in your own faith and belief there isn't a lot of harm you can come to at New Wine. You can enjoy the singing worship and pick the bits out of the talks and presentations without having to subscribe to the view that the only, the ONLY, way to respond to God is to go down the front and get ministered to by someone who will pray for you to have more Holy Spirit. I tended to pray quietly for a few moments and then slink off. I do not join the ministry team because I don't think that is what I understand by ministry.

(hat tip to Cartoon Church)

I do quite a bit of experimental cookery. Sometimes the results are odd or dubious. Sometimes they are quite nice. And sometimes they are better than anything I've had when eating out. Thinking about it, they seem to be at their best when freestyling vaguely close to traditional recipies. This is one of those.

(serves 2)

link to full text of statement

Article 5 then holds together the ideas that revelation is progressive, but that later revelation doesn't contradict earlier revelation. Articles 6-10 are about the doctrine of inspiration.

At this stage, it becomes clear that actually the authors are using "inerrancy" as a catch-all term for their doctrine of Scripture, even though many of the features they describe are not directly connected to inerrancy and although "inerrancy" is not the best term for it (IMO). Hence they're using the term in two different senses in the same document:

I think this distinction is an important one. In the past, certainly, my dislike of the term "inerrancy" has been because I do not think the normal English sense does sufficient work to cover all the bases it needs to. But its use as jargon means that more can be put into the word, which gives it that potential. It's still bad communication though.

As regards comments on Articles 6-10, I'm generally in agreement. They are holding together the idea that the Bible is both fully God's words and fully human words. Article 2 of the Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics makes the connection with the doctrine of Christ explicit.

However, I think 6-10 do contain a few potentially misleading generalisations.

ARTICLE 7:

WE AFFIRM that inspiration was the work in which God by His Spirit, through human writers, gave us His Word. The origin of Scripture is divine. The mode of divine inspiration remains largely a mystery to us.

WE DENY that inspiration can be reduced to human insight, or to heightened states of consciousness of any kind.ARTICLE 8:

WE AFFIRM that God in His work of inspiration utilized the distinctive personalities and literary styles of the writers whom He had chosen and prepared.

WE DENY that God, in causing these writers to use the very words that He chose, overrode their personalities.

I think to say that there is only one "mode of divine inspiration" is misleading. It is clear in Scripture that there are multiple modes, including visions (Revelation 1:9-11) and research by the author (Luke 1:1-4) as well as direct dictation by God (e.g. Revelation 2-3).

While there are certainly examples where it is clear God has used the distinctive personalities and literary styles of the writers (e.g. the differences between the gospels), there are other cases where he does seem to have overridden their personalities.

Here is Jeremiah (clearly with his personality not overridden at this point), seemingly complaining to God about God doing just that at other points.

O LORD, you deceived me, and I was deceived;

you overpowered me and prevailed.

I am ridiculed all day long;

everyone mocks me.

Whenever I speak, I cry out

proclaiming violence and destruction.

So the word of the LORD has brought me

insult and reproach all day long.

But if I say, "I will not mention him

or speak any more in his name,"

his word is in my heart like a fire,

a fire shut up in my bones.

I am weary of holding it in;

indeed, I cannot.

Jeremiah 20:7-9, NIV

So, in general, I agree. But I think that in assuming that there is only one mode for Biblical inspiration, and then generalising from some parts where it is clear (e.g. the gospels) to the whole Bible is unwise, as there are other parts where it is clearly different.

link to full text of statement

After the "short statement", come a series of 19 Articles, which draw out consequences of the statement. The first two are basic "Authority of Scripture trumps and is not derived from authority of Church, etc." statements.

In keeping with the traditions of the Church, the Articles then move into specific heresy spotting. But I'm not sure they do their job quite well enough

ARTICLE 3:

WE AFFIRM that the written Word in its entirety is revelation given by God.

WE DENY that the Bible is merely a witness to revelation, or only becomes revelation in encounter, or depends on the responses of men for its validity.

I can see the point of affirming that the Bible is in itself revelation rather than being a witness to revelation, as if the Bible were just a witness to revelation it would open the door to it being an imperfect witness to revelation. I also strongly agree that it does not depend on the response of men (or indeed women) for its validity.

I think I can also see the point of denying that the Bible becomes revelation in encounter, as that would make the response on the reader authoritative rather than the written word. However, I think that in doing so, the statement risks becoming internally inconsistent. If someone "reveals" that they are gay by writing it in their diary and never showing anyone, it is not revelation. Revelation needs to have an indirect object - it needs to be revealed to someone. Hence, while the Bible is truth about God when written and unread, it only becomes revelation when it is read. I think this is one area where Chicago seems vulnerable to postmodern critique - in this case the postmodern questions about the meaningfulness of communication.

Roughly speaking, the postmodern argument goes like this:

If I write someone a letter, the letter in itself is not communication. It does not have any inherent meaning. It is just a bunch of squiggles on a page. One person could pick it up and understand one thing by those squiggles; another person could understand something completely different by them.

The solution to the postmodern argument is in most situations to have predefined a meaningful and agreed system of communication - for example written English. In order to set up such a system (like to learn English), it is necessary to use spiral hermeneutics, where the meaning gradually becomes clearer, and commonly shared truth systems, such as the scientifically investigable physical universe.

The Bible can then be valid communication, because it was written in the well-understood languages of Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew, and so can have inherent meaning, given a knowledge of the languages, which can be taught (or translated, though there are difficulties with that). So it can be truth by God, about God without a reader, but I don't think it can be revelation without a reader.

ARTICLE 4:

WE AFFIRM that God who made mankind in His image has used language as a means of revelation.

WE DENY that human language is so limited by our creatureliness that it is rendered inadequate as a vehicle for divine revelation. We further deny that the corruption of human culture and language through sin has thwarted God's work of inspiration.

Yes, it is very important to say that language can and does convey truths about God. But I do not think anyone would say that language can convey the whole truth about God. I'm pretty sure that the Bible denies it too (e.g. Hebrews 1:1-4). Jesus is God's best self-revelation. Language is adequate for partial true revelation, but full revelation requires at least a person.

Now we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

1 Corinthians 13:12, NIV

The Chicago Statement begins with "A Short Statement", which has five points.

1. God, who is Himself Truth and speaks truth only, has inspired Holy Scripture in order thereby to reveal Himself to lost mankind through Jesus Christ as Creator and Lord, Redeemer and Judge. Holy Scripture is God's witness to Himself.

2. Holy Scripture, being God's own Word, written by men prepared and superintended by His Spirit, is of infallible divine authority in all matters upon which it touches: it is to be believed, as God's instruction, in all that it affirms: obeyed, as God's command, in all that it requires; embraced, as God's pledge, in all that it promises.

3. The Holy Spirit, Scripture's divine Author, both authenticates it to us by His inward witness and opens our minds to understand its meaning.

4. Being wholly and verbally God-given, Scripture is without error or fault in all its teaching, no less in what it states about God's acts in creation, about the events of world history, and about its own literary origins under God, than in its witness to God's saving grace in individual lives.

5. The authority of Scripture is inescapably impaired if this total divine inerrancy is in any way limited or disregarded, or made relative to a view of truth contrary to the Bible's own; and such lapses bring serious loss to both the individual and the Church.

So far, so good. It's clear (in my opinion), to the point. It keeps God's revelation in Jesus central - Jesus is God's supreme self-revelation, not the Bible (Hebrews 1:1-4). I can see that there are going to be questions about how we know what it affirms and what it does not (point 2 and 4). And perhaps it's necessary to keep that area fuzzy in a document designed to promote unity - we're not aiming for a complete and exhaustive exposition of the whole of Scripture - that's impossible. The purpose of this document is to describe something of how we should view Scripture.

The "short statement" seems eminently sensible.

One area that I keep revisiting in my thinking is the question of Biblical Inerrancy. To that end, I am re-reading the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy and will post some of my thoughts on it here in due course. I probably ought to say, by way of introduction, that I think I agree with what the people who wrote the Chicago Statement meant by it, and with the words they used, but I rather suspect that the words they used do not do enough work to cover what they meant by it.

Furthermore, I strongly suspect that inerrancy is a fundamentally Christian modernist point of view, and that it doesn't stand up too well to postmodern challenges. I'll also be trying to think about that, and referencing the Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics as well.

I do, however, think it is a thoroughly good thing that so many evangelicals from different backgrounds got together to agree on one of the key doctrines in evangelicalism.

Interestingly, I know quite a few Christian postmodern evangelicals who don't bother much about the whole inerrancy thing. They see, for example, the gospels as consisting of true stories, even if the details in those stories aren't necessarily factually accurate. Whether or not Mark was correct in saying that David took the bread at the time of Abiathar the high priest is pretty much irrelevant to their understanding of Scripture. I disagree (but then I would).

Telemarketers are annoying. It was a major reason I got rid of the landline at my last house (along with realising that it was cheaper just using a mobile). They are one of the reasons I only usually give out a number which leads to an expensive-to-call electronic voicemail box, which then e-mails me the voicemails as MP3s. But there is a way to deal with them.

Theoretically, the best way, as with spam and with annoying TV adverts, is not to abuse them (though that can be funny). After all, the telemarketers are just doing a job. It's not a great job, but it's slightly better than nothing. We don't blame people who work in factories which print porn for the consequent problems.

Theoretically, the best way is to stop people buying from telemarketers, or from internet spam, or products that have been advertised with annoying TV adverts. If telemarketing was not financially viable, people wouldn't do it. Ditto with spam. Ditto with annoying TV adverts. Ditto with door-to-door salespeople. Blame the idiots who buy from them.

Well, I've heard of people going into shock and failing to notice injuries. I even know a guy who only noticed his thumb had been ripped off after looking down at his hands. But this story really kicks it into a different league.

A Japanese biker failed to notice his leg had been severed below the knee when he hit a safety barrier, and rode on for 2 km (1.2 miles), leaving a friend to pick up the missing limb.

I bought a purple pepper from Sainsbury's the other day, because I wanted to know what it would taste like.

The cashier also said she wondered what it would taste like.

It was incredibly bland.

There seems to be this dumb idea that has got into the heads of food-selling people that people care primarily what food looks like rather than what it tastes like. Just try apples from a supermarket! And it's rubbish. I don't know where the idea comes from. I'd far rather have something that looked dodgy but was really tasty than something that looked all purple and shiny, but didn't taste of anything. And I think I'm in the majority for once on this.

Several of the Psalms contain what are often described as "deprecatory" sections - bits where the Psalmist is praying for God to break the teeth of / hurt / defeat enemies. And yes, I know Psalm 137:8-9 is worse than that.

Anyhow, Dale Ralph Davis has an interesting insight on this, while reflecting on how David treated Saul. David, of course, is credited as having written many of the Psalms, some even before he came king. Saul was David's predecessor as king, and spent several years trying to kill him because he was worried that David would take over. David had quite a few opportunities to kill Saul (e.g. 1 Samuel 24), but made a point of not taking them.

Davis points out two important features of deprecatory Psalms:

Should our attitude be different to 1? Maybe. In some cases, it is quite understandable to feel that way though. On a trivial level, I know I have briefly wanted nasty things to happen to people who (for example) turn left across the path I was trying to ride on a bike, in at least one case forcing me to skid off the road to avoid being hit. On a more serious level, the author of Psalm 137 had almost certainly seen the brutal destruction of his home city at the hands of the Babylonians, who had in all probability killed infants he knew by throwing them against rocks. In such situations, being angry and wanting nasty things to happen to people is understandable.

But given that anger, what should we do with it? Well, the message of the deprecatory Psalms is that we should pray about it and we should leave it to God to sort out. Revenge is not our job.

Does it take the message of the cross and the resurrection of Jesus to achieve the ends for which you are aiming in your preaching? If not, then you are not preaching the gospel, but offering self-improvement with a Christian veneer.

Philip Greenslade in Preach the Word (ed Greg Haslam)

Yesterday, the Church Times printed this article about the Oxford PPH review, which raises some interesting questions. Stephen Bates (notorious Guardian columnist) respun it here.

Nastinesses Mr Bates committed in doing so:

The broader question of what place confessionalism has in academia is an interesting one. In a secular university, there shouldn't be confessional requirements on posts. In a college training people for Anglican ordained ministry, there should. The obvious solution then seems to be to have two separate recruitment policies, but if staff at either are qualified to teach in both (i.e. academically respectable enough and confessionally in the right place), then there needn't be a problem with that.

I'm doing quite a bit of work on the Psalms at the moment - partly because I'm down to preach on one of them in a few weeks, and partly because I'm meant to know some of them especially well for my exams next year, so am getting a bit of study in early.

The commentaries on Psalms really are quite an odd bunch. Academic study of the Psalms for ages has centred on the idea of form criticism - when coming to look at any given Psalm, many commentators see their top priority as putting it into one of a dozen or so artificially-constructed categories, which don't always fit that well. Their second priority is then to try to back-engineer the Psalm to work out how it was written, preferably on at least three separate occasions by different people, who were taking earlier material and modifying it. Yes, sometimes there is a good but not conclusive case that that may well have happened (e.g. Psalm 89). Alternatively, they might try to work out what liturgical purpose this Psalm might have fulfilled. If that means inventing new major festivals which there is no evidence for, that seems to be ok as well.

One mind-numbingly obvious problem with all of that is that the Psalms are written as songs to be sung rather than texts to be classified or analysed for redaction layers, but many commentaries don't seem to go much further than that unless they see hints of pagan creation mythology (Psalms 74 and 89), at which point they get all excited.

Given that, four commentators seems to stand out as being worth reading, and two of them weren't in a position to take any notice of modern scholarship, some of which is actually worthwhile. Those four are:

It is quite possible that the multi-volume Baker commentary on the Psalms will be very good, but I haven't seen it yet.

One of the reasons I find it difficult to take militant atheists seriously is the quality of their arguments. I used to spend a lot of time discussing alleged inconsistencies in the Bible, and was used to all the examples they cited being rubbish. However, in academic circles, probably the most commonly cited "error" in the Bible is in Mark 2:26.

Jesus answered, "Have you never read what David did when he and his companions were hungry and in need? In the days of Abiathar the high priest, he entered the house of God and ate the consecrated bread, which is lawful only for priests to eat. And he also gave some to his companions."

Mark 2:25-26, NIV

The incident referred to is in 1 Samuel 21, where the high priest is Ahimelech. This is often cited as evidence that Mark got it wrong, and so when Luke and Matthew wrote their gospels later, they copied Mark but corrected his mistake by removing the reference to Abiathar. It is then used as evidence that Matthew and Luke used Mark as a source (which is quite possible - there is reasonable but not conclusive evidence that Mark was the first gospel to be written, and that it was based on the recollections of Peter, which would explain why it came to be the template for Matthew and Luke). It's also used as evidence that Mark is not a completely reliable source.

I'm studying 1 Samuel at the moment, so thought it would be a good opportunity to confront this alleged inconsistency and see if it actually stands up. It doesn't, of course.

The story continues in 1 Samuel 22. Saul finds out that Ahimelech helped David, and has that group of priests massacred. Well, all of them, except one, who escapes to tell David. Abiathar, son of Ahimelech (who then becomes high priest by virtue of being the only survivor). In fact, the conservation between David and Abiathar suggests that Abiathar had been there when his father had helped David (1 Samuel 22:22). Abiathar, being priest to David, ends up much better known than his father ever was. He gets 27 mentions by name in the Old Testament; his dad Ahimelech gets 11.

Mark records Jesus as saying that the incident was in the days of "Abiathar the high priest". Abiathar was not high priest at the time. On the other hand, he was alive at the time; he quite possibly witnessed the incident; he was the best known person there (apart from David) from the perspective of Mark's readers (and Jesus' listeners) 1000 years later; he became high priest as a result of that incident. I think that makes Mark's statement perfectly legitimate. After all, we'd be happy saying that William the Conqueror built up a large army in Normandy and then then invaded England in 1066, even though he wasn't called "the conqueror" until later. People don't seem to have a problem with saying that President GW Bush avoided fighting in Vietnam, even though he wasn't president at the time.

Once again, it looks as if whoever first came up with this as an objection to the reliability of the gospels was seriously desperate.

The rationale behind current abortion legislation is interesting. Indeed, it seems completely to ignore what seems quite obvious about the nature of the fetus.

Instead it seems to focus on the issue of viability - how capable the fetus is of survival without the mother.

Of course, on one level, this seems to be a ludicrous idea - a baby is not capable of independent survival at least until it can crawl, and in almost every case, for a long time afterwards. But it seems to me that the specific issue here is the dependence on the mother rather than on other human beings. After 24 weeks, the baby would need help to survive, but that help does not have to come from the mother.

Abortion legislation then seems to rest on the idea that no-one has an obligation to help another. If someone is lying bleeding by the side of the road, we do not have to call an ambulance. If we do not want to support our children, we can put them into the care of social services. If we do not want to support elderly relatives, ditto. If we do not want to support non-viable fetuses, we do not have to. But since there is no-one else who can support them other than the mother, the fetus is killed.