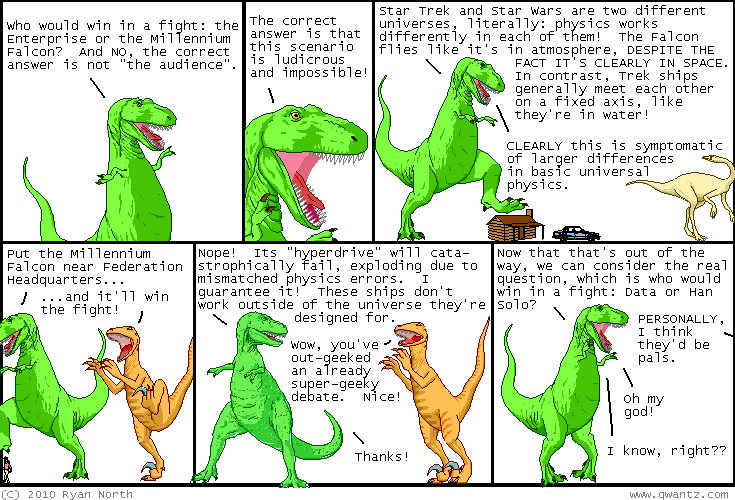

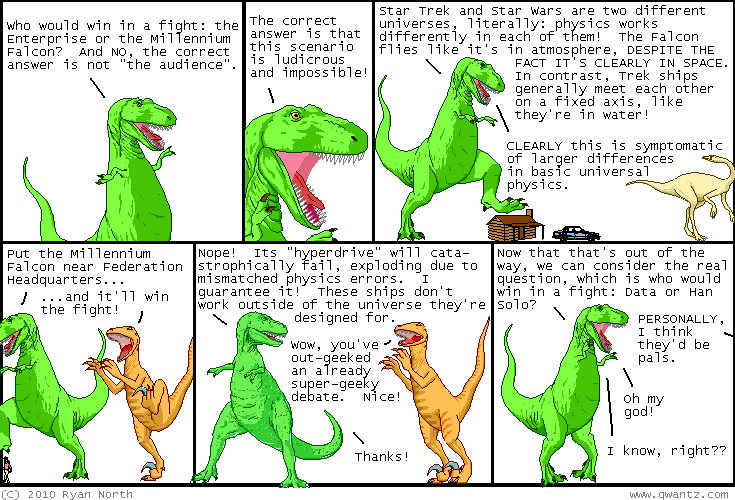

Dinosaur Comics is frequently just weird, but this is magnificent...

Dinosaur Comics is frequently just weird, but this is magnificent...

It's my day off. And this is wonderful.

HT to Stephen Pereira.

I got this for Christmas, and have had quite a lot of fun over the last few weeks watching it. It starts out as a sci-fi epic drama series about people who discover they have superpowers and try to stop a nuclear explosion in New York while avoiding the evil super-powerful series killer Sylar. Lots of end of episode sudden twists and cliffhangers, good fun if very very dark at times - it's probably gorier than Predator, for example.

BUT... there's always the slight danger of heading off into the whole soap opera about superheroes trying to live normal lives and solve everyday problems thing. As far as I can tell from watching episodes from later series, that's where it ended up, but it's only there as a slight weakness in series 1. I tend to like superhero films and so on - usually good escapist fun, but can't be doing with soaps. There are a few episodes in series 1 which seem to be setting that sort of thing up.

So great fun, but I don't think I'd go for series 2, 3 or 4, all of which have had much lower viewing figures than series 1. The ending of series 1 is fairly unsatisfactory and doesn't really fit with the rest of the series. Here is how series 1 should have ended for a more satisfactory conclusion IMHO:

Sylar makes another attempt on Claire, but is thwarted by Mrs Petrelli (who must have some kind of superpower). Hiro (who can time travel and teleport) uses his ability to create a squad of 6 or so Hiros, who then kill Sylar without any of the Hiros dying. And they kill him properly - decapitation or something, but not before Sylar has killed Mrs Petrelli. Peter Petrelli is filled with grief and anger, and starts exploding. Meanwhile, Hiro, DL and Nathan use their and Hiro's abilities to try to evacuate people from the blast area. Claire tries to save Peter, but only succeeds in sedating him after he has already done enough damage to fulfil the paintings. The series ends with someone coming across Sylar's head, only to find it has been cut open and his brain taken.

The 11th Star Trek film finally manages to break one of the long-running rules in Hollywood - that odd-numbered Star Trek films are rubbish. Many would say the even-numbered ones were too...

This is partly an attempt to do a film that comes just before the first series in the 1960s, and partly a reinvention of the whole franchise. And I have to say it's very well done. All the major characters from the first series are there, all well played by different actors but in such a way that it's believable that they're the same people. There are lots of nods to stuff in the original series - like a sense of fashion that could explain how on earth they ended up with the uniforms from the first series, and a scenario that explains how someone like Kirk ended up as captain. And it brings in some of the science from later series without the whole "particle of the week" solutions that dogged the later series of TNG.

The special effects are of course much, much better, even than the later series. And it's fun! (significantly helped by Simon Pegg as Scotty.) And the start of the film is incredibly good.

As a bit of a physics geek, I have to say I like what they did with the philosophy of time travel here. Not just having a consistent theory of it, but also playing with some characters having alternate theories of it...

It's worth adding that a friend of mine pointed me to this amusing video review...

I do like Google's April Fools' jokes.

Their one today - Virgle - is great.

Arthur C. Clarke has died. He was one of my favourite writers when I was a teenager, and had the great strength that most of his science made sense - he was for a long time more of a visionary populariser of science who could write than an author who liked science.

He'll pretty much always be credited with inventing the communications satellite. Actually, as I remember, he just popularised the idea which was already hiding in some obscure scientific literature.

He probably stands out to me as someone who was excellent at popularising and motivating people to love physics. He'll be missed.

Ishiguro is a very versatile and talented writer, and doesn't seem bothered by conventions of genre, which is a good thing; I guess he's quite like Margaret Atwood in that regard. This book probably best fits into the category of speculative fiction, rather like The Handmaid's Tale, except not quite as dark.

The central characters are three friends from an unusual English boarding school who come across each other later in life, and it's written as one of them looks back. A lot of the perennial major themes come up - memory, relationships and what makes us human. It's very well written. Yes, there's a central mystery to the book, as becomes apparent quite early. And if I hadn't pretty much figured it out by the end of chapter 4, the book would probably have been stunningly good rather than just very good. And lots of people don't - I guess I was somewhat more predisposed to get it than usual because of some of the stuff I've read and seen before.

There - I didn't give much away, I don't think.

One of the areas I used to be really interested in was the philosophy of time travel as represented in science fiction, especially with what happens if you change your own past, and how that ties into possible physical models of the universe. So there's the Back to the Future model, the Terminator model, the Quantum Leap model, the Sliders model, and so on. The problem if we ever do manage to travel backwards in time is knowing which model actually works. Maybe I'll write more on that at some point.

Anyway, here's a funny quote from Terry Pratchett, messing around with the idea in The Last Continent:

"I can't help thinking, though, that we may have... tinkered with the past, Archchancellor," said the Senior Wrangler.

"I don't see how," said Ridcully. "After all, the past happened before we got here."

"Yes, but now we're here, we've changed it."

"Then we changed it before."

And that, they felt, pretty well summed it up. It is very easy to get ridiculously confused about the tenses of time travel, but most things can be resolved by a sufficiently large ego.

The best word to describe this book is “epic”. Kim Stanley Robinson is best known for long and detailed science fiction – his Mars trilogy, for example, but this is much more clearly speculative fiction.

Science fiction and speculative fiction are fairly similar – in fact the nature of speculative fiction is quite similar to how science works – the idea is to change a few details of reality and see how that affects the rest of the world. In speculative fiction, of course, the results are speculative – it isn't like changing what surface something is sliding on to investigate friction. Speculative fiction, however, is much more respectable as a genre than science fiction...

Here, two main things are changed about the world. The Black Death kills almost everyone in Europe, instead of just a large proportion of them, and the story starts with the Mongol Hordes about to invade Europe, but who find everyone dead. The other thing that is changed is that reincarnation happens, which allows the book to take what some of the characters later describe as a Buddhist model of story-telling: following a group of people through successive reincarnations.

In doing so, Robinson cover nearly 1000 years of speculative history, through seeing the same characters reincarnated, sometimes as men, sometimes women, sometimes Muslims, sometimes Chinese, sometimes Indians or Native Americans, in lots of different contexts, so that we see the major turning points of his alternative history.

There's a few things I'd pick up on – he seems unaware of the Christian communities in South India, for example. Sometimes he gets self-referential, especially when discussing historiography or hypotheticals in history, which I can see might annoy some, but I think is quite clever.

It's a clever book, and a fun, thought-provoking read.

Here's a video I came across while on mission in Liverpool. A friend of mine was involved with the construction.... And yes, that's filmed in Manchester not Liverpool.

I've done some light reading over the last few weeks. Here are some of the books...

Shadow Puppets by Orson Scott Card is the third in the Shadow Saga by my favourite Mormon writer. It's not vintage Card sci-fi, like Speaker for the Dead is - it's more geopolitics a la Tom Clancy, but without the details of weapons and stuff. Still, a decent light read.

Blue Shoes and Happiness by Alexander McCall-Smith is another book in the Botswana series. They are great fun, likable and understandable characters, really well written. Light reading, but good fun.

The Letters of John by John Stott is a good and fairly light commentary on 1 John, 2 John and 3 John. ("Good" and "fairly light" by no means always go together when I use them.) He does use the Greek, but not in a heavy way and sticks to explaining the passage. Occasionally he overstates a case, but in general I found this a really helpful book to use devotionally.

This is a book review I wrote quite a while back on a previous site, but I'm reposting it here.

Dan Brown is a controversial author in the light of his book the DaVinci Code. Some of my pupils had told me this book was much better than DVC, and asked me some interesting questions about physics as a result of reading it. So I thought I probably ought to read it and write a review. Here it is...

Links to reviews of the DaVinci code can be found here and here (need to click past ads on the second one, but it's by a non-Christian, so fewer accusations of bias are likely).

The good points first. It seems to me to be very readable. Dan Brown seems to have an ability shared with the likes of Tom Clancy, John Grisham and J.K. Rowling to write long books that can be read in a single sitting. The suspense is generally handled very well, and brings some not especially well known physics into the public domain. I guess that is to be expected - Dan Brown is a professor of creative writing or something like that. But that is also at the heart of some of the bad points of this book.

Also worth noting is that Dan Brown is virulently anti-church in a very similar way to Philip Pullman, and that lies behind a lot of what goes on...

As in the DaVinci Code, Dan Brown is quite clever in the way he introduces spurious facts. He sets the book in a world very similar to this one, set slightly in the future, with lots of references to real people, places, statues and institutions. There is lots of truth here, but then you get people who are claimed to be experts in a field claiming things which aren't true at all, which means that people are likely to take the false on board with the true. Yes, there are fictional aspects to the story, and factual aspects to the world it is set in. What Brown does is that he adds some wrong fictional aspects to a factual world. And not just so the story can work - they are mostly ones which are directly anti-church.

However, again as with the DaVinci code, Brown makes sufficient factual mistakes in other supposedly parts of the book that if people know what is going on with, for example, high energy physics, they can see that he doesn't really know what he is writing about. I don't know much about Roman geography, art history, etc. I do however know about physics and some of the history of science and religion, and some random other stuff. I know little about the Masons and less about the Illuminati. I've only read the book once, not especially carefully, and these are the mistakes I bothered to note down. Yes, there are spoilers.

Physics mistakes first.

In the FACT section at the start, it claims that “antimatter is identical to physical matter except that it is composed of particles whose electric charges are opposite to those found in normal matter”. This isn't true. Antimatter in fact has all its properties opposite to normal matter except its mass / energy. So charges are opposite, but so are other properties such as lepton number, strangeness, charm, signs of interactions with gauge bosons (of which charge is just one example), etc.

The idea that matter can be created from energy is not especially new. In fact, it happens all the time when photons (“light particles”) get above a certain energy - equivalent to high energy cosmic rays. However, this produces no solution to the problem of where the mass / energy comes from in the Big Bang, since it seems that matter and energy are just different forms of the same thing. It is where either of them came from in the first place that is the problem. But see later for my comments on miracles. We'd also resist the idea that God is “energy” in the sense the word is used in Physics.

In fact, that is the way that antimatter is produced currently - a few atoms at a time. Producing ¼ of a gram would be.... difficult. It contains roughly 1.5e23 atoms.

On p96, Dan Brown strongly implies that electrons and protons are opposites, as are up and down quarks. They aren't. The opposites are respectively positrons, antiprotons, antiup and antidown. Particle physicists are original like that.

Also on p96, a physicist claims that using a vacuum to “suck” antimatter would work. It wouldn't. Vacuums (or vacuua) don't suck - it's the pressure of the air that causes air to rush into them. On the other hand, using the fact that matter and antimatter are bent opposite ways by a magnet is the way that matter and antimatter are currently separated, and it doesn't produce ¼ of a gram.

On page 108, the claim is essentially made that if you make larger quantities, it is more efficient than smaller quantities. This is true. But the gain in efficiency decreases as the quantity increases. The efficiency can never exceed 1. That is why antimatter can never be used as an energy source, because even if we make it using a perfect system, we can never get more energy out than we put in. Antimatter could potentially (in the distant future) be used to store energy, but not as a fuel.

Yes, CERN does exist, and yes, the Web was invented there. I'm not an expert on it - my closest connection is that one of my supervisors at university worked there half the time. I think Dan Brown has very much transferred the US idea of a lab onto Europe, and then scaled it up to account for the size of CERN. Needless to say, I think the chance of the director of CERN ever having a Mach 15 jet at his disposal are very very small. I also very much doubt they go for the whole crazy over-technologising of everything (rooms with air conditioning that can freeze everything inside, etc). Physics in Europe is notoriously underfunded compared to in the US. CERN even have their own page correcting a lot of the mistakes here.

There is a large part of the story spent running around Rome looking for a radio source. All they needed to do was set up three receivers at that frequency, see the time differences between the signals and use that to locate the source.

On page p53, “Islamic” is described as a language.

Brown translates “Novus ordo seculorum” is translated as “new secular order” (as opposed to “new order of the age”). The Latin “seculorum” doesn't necessarily have implications of “secular” (though secular is derived from seculorum in the sense of “of this age” rather than “set apart”). For example, the Gloria in Latin reads “Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto. Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper, et in saecula saeculorum.” (or secula seculorum). So “novus ordo seculorum” does not contradict “In God We Trust”. If you don't believe me, see here. Yes, of course there is Masonic influence in the US currency.

Brown claims that every story the BBC runs is “carefully researched and confirmed” (p289). Well, the examples I have known in real life as well as on the BBC haven't been.

The director of CERN says “There are no churches here. Physics is our religion.” This despite the fact that there are quite a few Christians who work at CERN, even in this story!

Christian belief is continually seen as false because it claims events happened which are contradicted by science. This is to make the same mistake as Hume. The argument goes something like this. “We know that such events are impossible, so we know that any claims they happened are false.” But how do we know those events are impossible? And why are they recorded? The people who recorded Jesus walking on water didn't think it was an everyday event. They knew it was normally impossible, which is why it was so important that it happened, because it showed that Jesus was not a normal man - that he could command nature and it obeyed, especially when that went against the normal way that nature works. If Jesus was God, then he could have commanded the world to do whatever he wanted to. God created the laws of the universe - he can tell it to do whatever it wants. The same goes for creation. Yes, the start of the universe cannot be explained in terms of the observed laws of the universe, as it involved a huge amount of mass / energy coming into existence from nothing. But God can do it - he is above the laws of the universe and they don't apply to him.

Incidentally, the twist at the end is nicked from a Father Brown story (GK Chesterton). Except, there the priest realises that it is being set up so that he seems to have risen from the dead, only for the “miracle” later to be exposed as a fraud. So he is totally honest about it from the start.

This links in to the general attitude to faith in the book. Faith is seen as involving a “suspension of disbelief” (p132) and as being something that, while useful for providing a moral framework, goes against the evidence. That is certainly a common view, but is not the traditional Christian one, nor is it the one taught in the Bible. As far as I recall, it was the view popularised by the Existentialist philosophers like Kierkegaard. The Christian view of faith is basically one of “trust”. On the basis of the available evidence, we decide to trust God. As we trust him more and more, we see that he is more and more trustworthy. Faith is not believing against the evidence; it is trusting our lives to God based on the evidence.

The famous (and wrong) “God of the Gaps” idea is also used on p43. Brown pictures religion and science as both about asking questions, most of which have now been answered by science, restricting religion to fewer and fewer questions. That isn't true at all. Here are some verses from the Bible.

God is more than we imagine; no one can count the years he has lived.

God gathers moisture into the clouds

and supplies us with rain.

Job 36:26-28, CEVThe sun knows its going down.

You make darkness, and it is night,

Psalm 104:19-20, MKJV

The writers, even though they were writing around 1000BC, clearly have a reasonable idea of how rain happens (moisture gathering in clouds) and that night is caused by the Sun going down. But that does not stop them from ascribing those same actions to God. The Bible does not say that the two are competing explanations - it treats them as complementary. Both descriptions are true.

However, the main area where Brown's treatment of history is hugely different from real life is in the historical relationship between science and Christianity. For example, on p50, Langdon claims that “since the beginning of history, a deep rift has existed between science and religion.” That just plain isn't true. While there were personal tussles and power struggles between scientists and the religious establishment (as happened with Galileo and Bruno), in many ways modern science sprung out of Christianity. The view that they have always been at conflict was actually invented in the late 1800s as part of the debate over Darwinism.

Many of the early opponents of Darwinism were Christians, not always because they believed the Bible taught it to be wrong, but because the evidence was shaky and because they had an alternative theory in direct creation, whereas the atheists had no alternative theories. To discredit these Christians, books were written which distorted the earlier debates with Galileo by saying that the church at the time taught that the Earth was flat and that the church had always opposed science. Neither was true. [At the time, the Roman Catholics had taken on board a lot of Greek philosophy, including Ptolemy's description of the Earth as a sphere at the centre of the universe. This was by no means held by all Christians, and isn't taught in the Bible.] There's a lot more detail on this in Kirsten Birkett's book Unnatural Enemies. Kirsten, if I remember correctly, has a PhD in History of Science, so knows what she is talking about.

See, for example, here or here for stuff on Galileo.

The current hostility is also hugely exaggerated.

I am not aware of any opposition to Particle Physics from Christians for example on principal. There may well be some on the grounds that particles physics tends to be very expensive, and many (Christians and non-Christians) think the money could be better used.

For example, the Vatican is said to be creationist on p159. Odd, since the (now previous) Pope is on record as saying that evolution is not incompatible with Christian belief.

And yet, the Vatican is strongly opposed to in vitro fertilisation, as it involves the production of many fertilised eggs, most of which are destroyed. They are not opposed because it is science, but because they believe it involves the destruction of human life. It is therefore incredibly unlikely that a priest and a nun would be allowed to go through the procedure, as they would need to have done thirty-something years before the story is set.

Of course, Brown's argument is more with the Roman Catholic Church, and especially with its claims to absolute truth than with Christianity itself. I am no great fan of the Roman Catholic Church; I agree that the concentration of power has in the past led to horrible abuses of that power, but the claims for the authority of the Christian message are shared by many other groups of Christians who do not abuse the power in the same way. To an extent, Brown attacks the part of Christianity most open to such attack - the Catholics, and then implies the same is true for all other groups, when his argument holds even less for them than it does for the Catholics.

All in all, an interesting read, but it would be easy for this book to mislead people who did not already know what Christianity taught and something of the history involved. I think that's the idea.

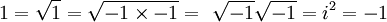

Here's an interesting maths fallacy (and thanks to DH for pointing me to the page with it on).

I also had a nifty scientific idea this morning. I was watching Firefly (TV sci-fi series, they only ever made one series of it) yesterday. One of the odd details is that all the planets and moons are meant to be in the same stellar system, but they all look remarkably like Earth. Odd that.

Anyhow - I was wondering how one might go about getting enough light and heat from the Sun to make them warm enough for habitation, and I figured that putting a lens at the Lagrange Point could well do it. Then I realised that such a lens would need to be pretty huge - nearly planet-sized even, and so would effectively require you to demolish a planet / moon to make it.

Then I thought of an interesting way round - use a Fresnel Lens (like those magnifying sheets you can get). You'd still need a big lens, but it'd be essentially 2D rather than 3D, so would need far far far less material and at least be possible.

It's my birthday! Woo!

Nano-robots go wild and kill people. Written by Michael Crichton, hence:

Very much in the Andromeda Strain / Jurassic Park genre.

While I'm busy doing book reviews, I might as well mention Xenocide, by Orson Scott Card, which I read last week as a treat just after I passed my driving test.

It's book 3 in one of the best sci-fi series I've ever read - the Ender Saga. I don't think I've written reviews of any of the others, so I'll quickly outline what happens.

In book 1 - Ender's Game, Earth is recovering from a devastating attack by an alien fleet, who they narrowly beat off. To make sure that it doesn't happen again, they are finding (and even genetically engineering) exceptionally talented children and training them in space tactics, warfare, etc. Ender is one of them, and this book basically goes through his childhood, especially his time in Battle School. It's pretty violent in places (read kids occasionally beating each other to death, general warfare stuff). What the book is especially good at is portraying what life is like for exceptionally bright young people (especially Ender, his gentler sister and his more ruthless brother) surrounded by less capable older people.

Book 2 - Speaker for the Dead - takes place thousands of years later (Earth time), with some of the same characters having been kept alive by virtue of being on ships travelling at nearly the speed of light (the physics of it is fine). It's mainly set on a planet where the human colonists are struggling to come to terms with a local intelligent species known as "the piggies". It's an excellent exploration of what it means to know other people and to understand other people.

Book 3 - Xenocide - is set on the same planet a few decades later. They are faced with the very real possibility that of the 4 (or indeed 5) known intelligent species, all might be killed in a forthcoming war, unless one is destroyed sooner. In writing this, Card includes one of the great discussions of what it means to be free, albeit by invoking some weird sciencey stuff. But that's allowed for SF writers, as long as they are clear what they are doing, and that they are using it to explore real issues. And OSC does that very well indeed.